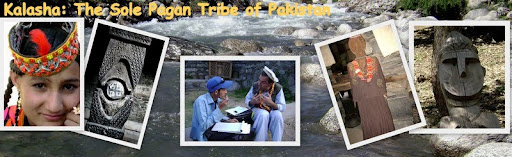

KALASH

– THE VALLEY OF KAFIRS

Minority: Kalash

Country: Pakistan

Author: Rabia Shahid

How would it feel to be part of a culture that is practiced by just 3000 people

in a global population of billions? The Kalash culture is indeed unique.

Situated in the midst of a Muslim majority population, the three little

villages of Kalash are an excellent example of the preservation of a community

which is distinct in its ethnicity, language, religion and culture.

The Kalasha community is the

smallest minority in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. The 1973 Constitution of

Pakistan under Article 260 only recognizes religious minorities, ignoring the

existence of other types of minorities. Kalash is located at a height of 1900

to 2200 meters in the Hindu Kush mountain range between the Afghan border and

Chitral valley in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province , Pakistan. It primarily

consists of the three villages of Birir, Bumburet and Rumbur, locally known as

“Kafristan” (land of the infidels, coming from the word Kafir which is an

Islamic term for an unbeliever). The valleys are situated to the southwest of

the town Chitral at a distance of 40, 43 and 36 kilometers respectively.

Historically, Kafristan included the

region of present day Nuristan in Afghanistan and the three Kalash valleys. It

is believed that in 1320 the population of the Kafirs was 200,000. This has now

reduced to a mere three to four thousand. In 1895, Amir Abdul Rahman, the King

of Afghanistan, conquered the Afghan region of Kafristan and forced the Kafirs

to convert to Islam. It was at that time that the Afghan Kafirs migrated to the

Chitral valley to avoid threats of conversion. The people of Chitral gave them

a warm welcome, allowing the community to exist and practice their religion and

culture without any restraint. According to Israr-ud-Din (1969), the Kalash

ruled Southern Chitral for around three hundred years, until they were

overtaken by the Khowar speakers. Thereafter, some Kalash retreated to the

valleys they occupy today and some became Khowar speakers and converted to

Islam. The cordial relationship between the Chitralis and the Kalash people who

refused to come under the religious and political influence of the Khowars

exist today, even though radical Islamization of the country has posed some

challenges for them. As per Kalash custom, once a person converts to Islam he

or she is banished from the community and cannot revert. Today the number of

Kalasha speaking converts living in the vicinity of the valleys exceeds the

number of the original polytheistic Kalasha.

Origin of the Kalash community in Pak-Afghan

region

The historic origins of this community are shrouded in mystery and controversy.

Different theories exist as to the origin of the Kalash people, the most

popular and grand being that they are descendants of Alexander the Great. The

other two theories propose that they are an indigenous population of South

Asia, or as suggested in Kalash folk songs and epics that their ancestors

migrated to Afghanistan from “Tsiyam”, which is identified by some

anthropologists as the area of Tibet and Ladakh.

There are many pieces of evidence

presented by all schools of thought in this matter, making it difficult to

trace the true origin of this minority. The Greek influence is found in the

architecture, music, games, food, wine, and even in the blond hair and blue

eyes of the Kalash. Yet at the same time certain genetic studies, like the

study by Rosenberg, have come to the conclusion that this race is a separate

aboriginal population with little influence from outsiders. Another genetic

study “Worldwide Human Relationships Inferred from Genome-Wide Patterns of

Variation (2008)” also came to a similar conclusion and categorized the Kalasha

population as a separate group of people.

The Kalash Language – no written

documentation

Kalash is a Dardic language which belongs to the Indo Aryan Group of the

Indo-Iranian group of languages, which is itself a sub group of the larger

Indo-European Group. Kalash is further categorized into the Chitral sub-group

of languages, next to only one other language, Khowar. Though the two languages

are different, they nonetheless share some similarities, and due to the

increased interaction between the native speakers of these two languages there

are now more bilingual people speaking both Khowar and Kalash as there were in

the past.

The most distinct characteristic of

the Kalash language, along with some other local languages of the Chitral

District, is that it is purely oral and has no written manuscript. Thus all the

folklore, customs and traditions have been handed down from generation to

generation through word of mouth without any written documentation. Absence of

a written manuscript, coupled with the fact that around four thousand people

speak this language, has placed it on UNESCO’s list of critically endangered

languages.

However, the people of Kalash

maintain great pride in their language and the usage of this language has not

decreased in the Kalash valleys over the passage of time. It is normal to see

Kalash people interacting in their language in their homes, streets and markets.

The most popular second language with the Kalash people is Khowar, but it is

only used by people who go outside the Kalash valley for business or work, thus

women and children are in a majority of the cases monolingual.

Recently many attempts have been

made by local Kalash people in cooperation with foreign NGO’s to preserve the

Kalash language via its documentation. In 2000, Taj Khan Kalash, a local

Kalashi, organized the first Kalash Orthography Conference in Islamabad.

Working in collaboration with international linguists and researchers, the

first alphabet book of Kalash language in Roman script was published. Efforts

are now being made to teach the Kalash people how to adjust to this

evolutionary change in their language and learn how to write it. Significant

research has taken place in the codification of this language; the dictionary

of the codified Kalash language is even available online today, increasing the

possibility for linguists and researchers to study this language in more

detail.

Despite efforts to preserve the

language, the community faces tough challenges in preserving it for future

generations. It was in 1989 that the government allowed the Kalash to use their

language as the medium of instruction, despite the uniform syllabus rule in the

country. The majority of the teachers are Khowar native speakers, resulting in

the instruction language to be Khowar rather than Kalasha. Thus, the major

logistic hurdle in the teaching and preservation of the language is a lack of

schools teaching the Kalash language and using it as a medium of instruction.

Kalash Culture: Festivals and Purity

The Kalash culture has been the centre of fascination for tourists, the

British, and many anthropologists for years. Compared to the conservative

Islamic majority, the Kalash valley, which is well protected within the

mountains of Hindu Kush, is the home of polytheists for whom dance, wine and

mingling between the sexes is not a taboo.

Nature plays a spiritual role in the

lives of the Kalash people and this is reflected in the gods they worship and

the customary festivals of the community. Among many festivals celebrated, the

three main ones are the Joshi festival celebrated in May, the Uchau festival

celebrated in autumn, and the most important Chaumos festival celebrated for

two weeks at the winter solstice. Festivals are a way to offer thanks to the

gods for the abundant natural resources gifted to the people of the valley. The

Kalash people like to celebrate, and a typical festival involves singing,

dancing, offering bread, cheese, meat or wine, and at times a sacrifice. The

women of the community take active part in the singing and dancing at the

festivals. Unlike Muslim societies, there is no concept of segregation in the

Kalash society. Men and women freely interact with each other. Women are free

to choose their husbands, while sex and love affairs are a common occurrence.

Kalash women are easily

distinguishable due to their unique dress. They always wear a long black gown

stretching on until their ankles. The gown is adorned with colorful beads and

cowrie shells and accessorized by bead necklaces coiled around the neck,

accompanied by an ornamental headdress. Men wear the traditional national dress

of Pakistan with a woolen waistcoat.

The Kalash culture is very

particular about the pure and impure. A particularly intriguing tradition is

the tradition of Bashli. Bashli is the tradition of sending menstruating women

and the ones giving birth to a special home. They can only come out of the home

after the menstrual or child birth period is over. During such a state a woman

is considered impure. Gods are considered pure, and between impure women and

pure gods there are degrees of pure entities. A man is considered more pure

than a woman, and an innocent boy would be more pure than an adult. There are

also designated pure areas inside houses where women cannot go because they are

considered impure.

Discrimination and attempts to

convert to Islam

Kalash is a pastoral community which is heavily dependent upon agriculture and

livestock. Over the years tourism has also become a major source of income for

the Kalash people. However, generally the area remains underdeveloped due to

its remote location and also because of the apathy of the authorities. The

Kalash people are poor and face discrimination when it comes to jobs. Money

that comes in from tourism seldom comes in the hands of Kalash people as

majority of the hotels in the vicinity are owned by non-Kalash.

Availability of cheaper

alternatives, coupled with poverty, is endangering the use and production of

rich Kalash gowns worn by women, and of certain foods and drinks, especially

the production of wine, which is often expensive. Infrastructure is weak as

there are not enough roads, hospitals, high schools and universities for the

Kalash. This forces many families to convert to Islam; a trend which is

detrimental to the existence of the Kalash. The religious sites of worship are

also in danger due to attacks by Islamic fundamentalists and a lack of funds

for maintenance.

Lack of media causes discrimination

The discrimination is allowed to continue due to the absence of any medium of

communication that would connect the Kalash communities with the outside world.

There are no Kalasha newspapers, radio or TV stations. Other than a few

websites personally made by some Kalash individuals, there is no official

presence of the Kalash community in the media in the form of a group or

organization. Any development in the area of preservation of the valley and its

culture has primarily come from the Ministry of Culture and Tourism and

international aid groups interested in the region. Major aid and development is

devoted to improving and facilitating cultural festivals, tourist information

and environmental protection measures. According to Saifullah Jan, an activist

who has represented the Kalash people at many forums, more resources need to be

devoted to basic infrastructure like schools, roads, and health facilities to

ensure the survival of these indigenous people. Also, less interference should

be made into matters of farming and irrigation techniques, which according to

him are something that the people are already well versed in.

Bibliography:

1. SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 5 LANGUAGES OF CHITRAL.

Kendall D. Decker 1992. National Institute of Pakistani Studies Quaid-i-Azam

University and Summer Institute of Linguistics.

2. The Kalash – Protection and Conservation of an Endangered Minority in the

Hindukush Mountain Belt of Chitral, Northern Pakistan. IUCN – The World

Conservation Union.

3. Minority Rights Group International, Report on Religious Minorities in

Pakistan, by Dr. Iftikhar H. Malik.

4. Enclaved knowledge: Indigent and indignant representations of environmental

management and development among the Kalasha of Pakistan. Peter Parkes,

University of Kent, Department of Anthropology, United Kingdom 1999

5. THE KALASHA PAKISTAN) WINTER SOLSTICE FESTIVAL. Alberto Cacopardo and

Augusto Cacopardo Liceo Scientifico “G. Ulivi” Borgo San Lorenzo. Ethnology, Vol.

28, No. 4 (Oct., 1989), pp. 317-329. University of Pittsburgh- University of

Pittsburgh- Of the Commonwealth System of Higher Education.

6. Low Levels of Genetic Divergence across Geographically and Linguistically

Diverse Populations from India. Noah A. Rosenberg, Saurabh Mahajan, Catalina

Gonzalez-Quevedo, Michael G. B. Blum1, Laura Nino Rosales, Vasiliki Ninis,

Parimal Das, Madhuri Hegde, Laura Molinari, Gladys Zapata, James L. Weber, John

W. Belmont, Pragna I. Patel.

7. Worldwide Human Relationships Inferred from Genome-Wide Patterns of

Variation. Jun Z. Li, Devin M. Absher, Hua Tang, Audrey M. Southwick, Amanda M.

Casto, Sohini Ramachandran, Howard M. Cann, Gregory S. Barsh, Marcus Feldman,

Luigi L. Cavalli-Sforza, Richard M. Myers.

8. Proceedings of the third International Hindu Kush Cultural Conference – A

minority perspective on the history of Chitral: Katore rule in Kalash

Tradition, Peter Parkes