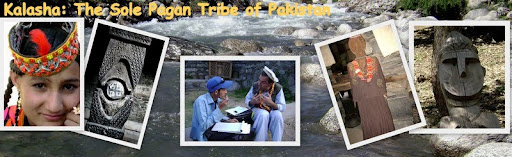

Kalash: Culture shock

Sunday Magazine Feature

By Obaid Ur Rehman

Published: June 26, 2011

The reason that traditionalists have threatened the Kalash in recent years is that the Kalash adhere to a polytheistic tradition based on ancestor worship.

“Every week we get threats from people who ask us to abandon our traditions,” says Fida, a resident of Bamorat village of the Kalash Valley

The Kalash live in about 12 villages in the valley, which is full of lush green fields and natural springs. The Kalash villages are accessible from Peshawar and Gilgit over the Lawari Pass and Shandur Pass Islamabad or Peshawar

The origins of the Kalash tribe are shrouded in doubt and speculation. Some historians believe that these people are the descendants of Alexander the Great. Others say the Kalash are indigenous to Asia and come from the Nuristan area of Afghanistan Afghanistan from a distant place in South Asia called ‘Tsiyam’, a place that features in their folk songs. However, it has been established that the Kalash migrated to Chitral from Afghanistan Afghanistan

But by 1320 AD, Kalash culture had begun to fall. Shah Nadir Raees subjugated and converted the people to Islam, with the villages of Drosh, Sweer, Kalkatak, Beori, Ashurate, Shishi, Jinjirate and adjacent valleys in southern Chitral among the last subjected to mass conversion in the 14th century. By the time the Amir of Afghanistan forcefully converted the Red Kafirs on the other side of the border to Islam in 1893, the Kalash were living in just three Chitral valleys, Bhumboret, Rumbur and Birir. The villages of the converted Red Kafirs in Chitral are known as Sheikhanandeh — the village of converted ones.

Today, the Kalash are popular with domestic and foreign tourists because of their unique culture. The Greeks have recently shown great interest in the area and one NGO reportedly funded by the Greek government is doing a great job protecting this ancient civilisation. Unfortunately, according to a survey conducted by an NGO, the Kalash population decreased from 10,000 inhabitants in 1951 to 3,700 in 2010, motivating conservation experts, development workers and anthropologists to put in greater efforts work to preserve Kalash culture. The Kalasha Dur — the “house of the Kalash” — is the outcome of these efforts: a museum which houses artifacts from Kalash culture.

The reason that traditionalists have threatened the Kalash in recent years is that the Kalash adhere to a polytheistic tradition based on ancestor worship. They also worship 12 gods and goddesses dominated by the main god Mahandeo. Their myths and superstitions centre around the relationship between the human soul and the universe. This relationship, according to Kalash mythology, manifests itself in music and dance, which also contribute to the pleasure of gods and goddesses. In their festivals, music and dance are performed not only for entertainment, but as a religious ritual. The Kalash celebrate four major festivals commemorating seasonal change and significant events in agro-pastoral life. These festivals are Joshi or Chilimjusht, Uchal, Phoo and Chowmos. The Kalash celebrate these festivals by offering sacrifices on altars, cooking traditional meals and dancing to traditional music during the week-long events.

The Kalash have kept alive their ancient traditions, including superstitions about menstruation and pregnancy. During these times, women are secluded, and live in a place called Bashali. Each Kalash village has a Bashali outside the settlement, and though women are allowed to work in the fields they are not allowed to go home. The Betaan or Shaman plays an important role in Kalash culture. He makes prophecies during religious rituals, and seeks the help of fairies to make prophecies come true. Another important practice in Kalash mythology is astronomy. The Kalash believe that a new sun is born on December 21 and that the new sun affects the flora and fauna of the land.

This civilisation is now wasting away as some Kalash families have either gone underground or left the area. This may be a great blow to Chitral which pockets millions of rupees from tourism every year.

“We don’t want to leave this land,” says Gollaya, a villager in Bamort. “But we are afraid of people who threaten us if we do not bow down to their wishes. The government and local

administration is protecting us, but we still feel insecure.”

administration is protecting us, but we still feel insecure.”

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, June 26th, 2011.